(Public Post): Understanding Structural Dissociation and the Value of Noticing 'Parts'

Healing From FSA: What adult survivors of Family Scapegoating Abuse (FSA) need to know about Complex Trauma and survival parts

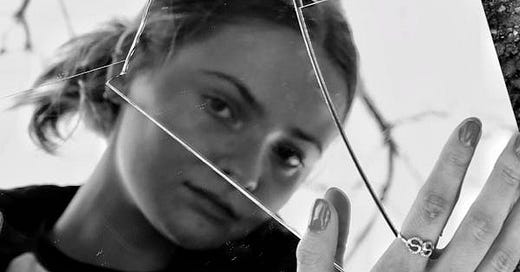

When children are chronically traumatized within their family-of-origin, they can develop a form of dissociation known as Structural Dissociation, whereby the personality lacks integration and expresses itself through 'parts'. But it is never too late to experience your innate wholeness...

Subscribers: Share or restack quotes from this article by highlighting it.

Introduction

The research I conducted over a ten-year period on what I eventually named Family Scapegoating Abuse (FSA) suggests that it is often the family Empath or Highly Sensitive Person (HSP) that ends up in the ‘Family Scapegoat’ or Identified Patient (IP) role.

Because children who are emotionally sensitive tend to have stronger reactions to adverse life events, they will be profoundly impacted by toxic family dynamics, resulting in their possibly developing complex trauma (C-PTSD) symptoms. If the toxicity and trauma experienced is chronic and severe, structural dissociation within their personality may result.

Why Structural Dissociation Develops

When a child is chronically traumatized within their family-of-origin, they can develop a form of dissociation known as structural dissociation, whereby the personality lacks integration and expresses itself through 'parts'.

As discussed in my introductory book on FSA, Rejected, Shamed, and Blamed, children are dependent on their (scapegoating) caregiver(s) to survive - most typically their parents.

When a parent acts in scary, harmful, non-nurturing, and unjust ways, the child will find themselves in the position of fearing the care-giving figure that they need to safely attach to in order to survive. This sets the stage for disorganized attachment and attachment trauma to develop.

Researchers have found that dissociative symptoms are associated with disorganized attachment. Children in a relationship with unstable, unpredictable, or even traumatizing parental caregivers will have difficulty holding a consistent view of the parent and of themselves.

And yet, to survive physically and psycho-emotionally, the dependent child must somehow attach to their unsteady, unstable (and at times unsafe) caregiver. Negative feelings that cannot not be safely expressed toward the non-nurturing, ‘scary’ parent will instead be turned (unconsciously) inward toward the child’s own developing self, as this is a psychologically "safer" thing to do, given the dependent position the child is in. This is how the 'false’ or 'survival' self, with attendant self-alienation, fragmentation, and split-off ‘parts’, first begins.

As the child begins to operate from their 'survival self' to function within the threatening, traumatizing environment they find themselves in, various (traumatized) survival 'parts' may begin to take hold within their psyche, parts which are rooted in the trauma responses of 'fight', 'flight', 'freeze', 'fawn'/'submit', ‘force’ and 'attach' (also know as “the cry for help" trauma response).

These non-integrated survival parts of the child's personality are emblematic of structural dissociation. The personality has, in a sense, fractured into different intrapsychic 'parts' or ‘selves’ as a means of coping in a hostile, frightening, rejecting, and shaming environment. There also remains a functioning, 'normal' part that "keeps on keeping on" as it goes about the business of everyday life, such as school, household chores, socializing, etc.

How Structural Dissociation Manifests in Adulthood

In my Psychotherapy and FSA Recovery Coaching practices, a client with structural dissociation may have difficulty regulating their emotions and will report experiencing chronic feelings of emptiness within.

Previous mental health providers may have diagnosed them as having Borderline Personality Disorder, Histrionic Disorder, Bipolar Disorder, an Anxiety or Depressive disorder, or Bipolar disorder, although they may not relate to the diagnosis given as it fails to capture the full scope of what they are experiencing.

Nearly all trauma survivors will have dissociative symptoms. xperiencing primary structural dissociation does not mean that you have Dissociative Identity Disorder (having several distinct identities that seem to exist and operate separately from each other, referred to as tertiary structural dissociation).

Learn more about Structural Dissociation theory and primary, secondary, and tertiary structural dissociation here.

The 'Normal' or 'Taking Care of Business' Part

In structural dissociation, each 'part' can have its own unique personality with its own feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. This can result in the appearance of instability and emotional dysregulation as the adult survivor swings rapidly between different states of being - one minute happy, excited, confident, or hopeful; the next minute depressed, empty, helpless, or numb.

Most FSA adult survivors who struggle with structural dissociation have a strongly developed high-functioning, 'normal' part that helps them to carry on with the routine and necessary aspects of their lives. This part may be incredibly competent and efficient, as it exists separately from the parts that feel vulnerable, exiled, rejected, hurt, shamed, helpless, and sad.

However, even while everything seems fine on the surface, parts that are rooted in the traumatized self can be activated in the psyche when 'triggered'. This can lead to unexpected and (at times) regressive and uncontrollable thoughts, feelings, reactions, and behaviors that can be highly painful and confusing to the high-functioning FSA adult survivor, particularly when the ‘fight’ trauma response is activated.

Assessing Structural Dissociation in a Treatment Setting

As a trauma-informed clinician, I am likely to assess for structural dissociation if a client reports experiencing some of the following symptoms during the intake process (or later on during treatment):

Feeling disconnected from their body, like they are outside of themselves or "far away"

Feeling separate from everything around them

Feeling like the world around them is distant or unreal

Unable to make decisions

Feeling chronically numb and emotionally detached

Compartmentalizing information

Frequently losing / misplacing things

Finding themselves somewhere with no idea as to how they got there

Operating from two or more streams of consciousness (e.g., showing up in therapy as distinctly different people from week-to-week)

Lack of motivation and stamina (leaves tasks uncompleted; self-sabotages)

Feeling confused about their identity ("I don't know who I am")

Doing things they have no memory of doing later

"Zoning out" (escaping) via addictive / self-destructive behavior

Isolating and counter-dependency (lacks trust in others and fears doing so, which can look like paranoia)

Somatic symptoms (e.g., migraines; unusual tolerance to physical pain)

Experiencing partial amnesia (gaps in the recall of events; unable to remember personal information)

Having several distinct identities that seem to operate separately from each other (this would indicate Dissociative Identity Disorder).

Treating Complex Trauma and Working With Dissociated Parts

I searched long and hard for a complex-trauma treatment method that would help both me and my FSA adult survivor clients. My search eventually led me to the work of Janina Fisher, who was an early colleague of trauma researcher and author Bessel van der Kolk (author of The Body Keeps the Score). If you haven't yet read Fisher's book, Healing the Fragmented Selves of Trauma Survivors: Overcoming Internal Self-Alienation, I strongly encourage you to do so (I use Fisher's workbook, Transforming the Living Legacy of Trauma, with the FSA adult survivors in my practice as well).

In addition to the seminal work of Bessel van der Kolk, Fisher's understanding of trauma has been informed by the work of various respected trauma researchers and theorists, resulting in her adapting a Structural Dissociation model as the basis for her trauma treatment methods.

This Structural Dissociation model used by Dr. Janina Fisher theorizes that trauma (including complex trauma) results in the personality splitting off into a “going on with normal life” part (as discussed above), while non-integrated trauma-based survival parts of the personality form as coping mechanisms in response to overwhelmingly stressful or harmful environmental or relational experiences.

Per Fisher, traumatized clients with structural dissociation symptoms identify with one part or another at different times to the exclusion of their other parts, believing that they are that part, rather than a larger, 'whole', integrated self that contains all the parts. Such clients may feel anger (a 'fight' / attack response) one minute and an urge to flee / escape (the 'flight' response) the next. Their internal world feels chaotic and confusing, and is distressing for not only the client, but sometimes their therapist as well!

A Healing Pathway for Structural Dissociation

Drawing upon Schwartz’s Internal Family Systems model (IFS) and from Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, Fisher teaches her clients how to “unblend” from their parts by helping them see their parts through their 'noticing', witnessing, and non-attached mind.

Using this mindfulness-based approach, Fisher then assists her clients in getting to know and befriend their (traumatized) parts so that these parts (which are regressive in that they exist as the age they were when first traumatized) can join the client's adult Self and eventually receive from the client what they so desperately needed when they were young: Love, compassion, understanding, nurturing, and acceptance.

Via this method of first witnessing, then integrating, their traumatized parts, the client's personality gradually re-integrates, resulting in their being able to experience a sense of internal wholeness, inner continuity, and stability. This in turn helps the adult survivor to feel safe within themselves, giving them the strength to mourn their various losses and begin to come to terms with their traumatic memories.